How do we evaluate the impact of our stories?

Photo Credit: Animating Democracy

Not only can storytelling be evaluated within limits, but it can also serve as a method of evaluation—providing insight into the change a project makes. Here’s how to make the process useful and relevant.

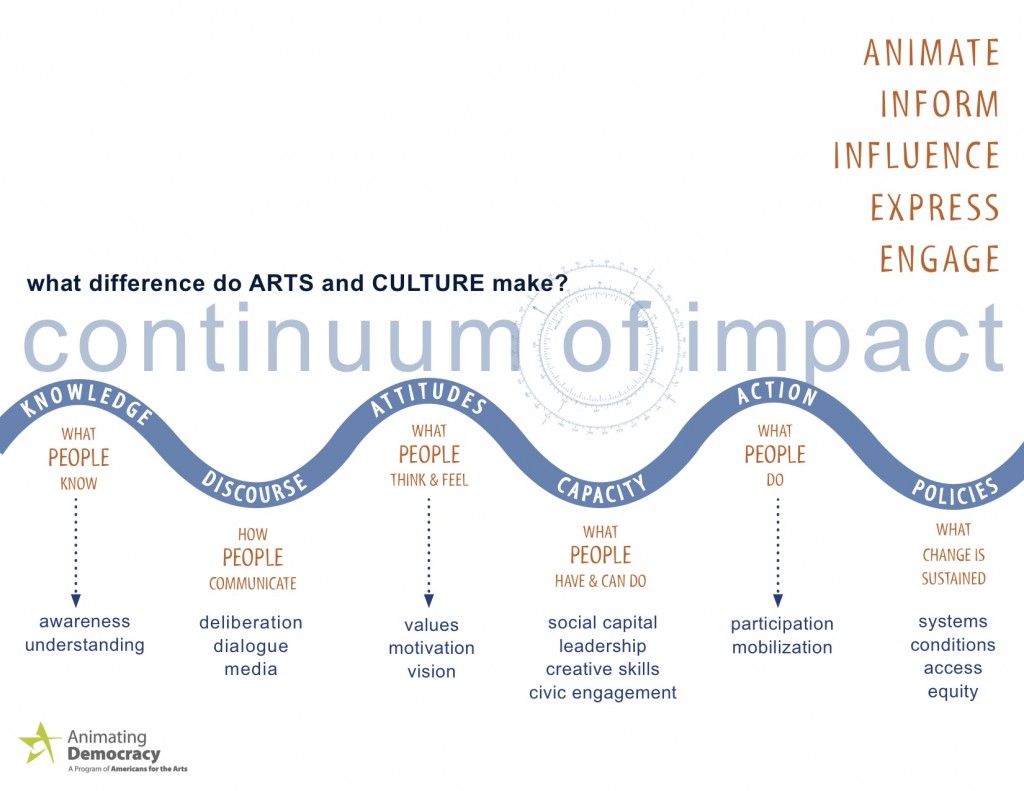

Clarify Your Goals Before evaluating whether your storytelling met its goals, you must clearly define those goals. Are you aiming to inform the public? Shift attitudes? Spur specific behaviors or policies? The Animating Democracy initiative by Americans for the Arts offers a framework of social-impact indicators that helps organizations assess changes in knowledge, attitudes, actions, and policy outcomes. This can guide both the design and measurement of your project.

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”—William Bruce Cameron

Going too narrow may yield obvious findings; going too broad can make the data meaningless. The right approach lands where your capacity to evaluate intersects with your desired impact.

Define Metrics and Methods Once your goals are clear, ask what success will look like. Will you see more volunteers? Greater media coverage? An uptick in donations? Turn these into measurable metrics over a defined time period. For instance, if storytelling is part of a fundraising campaign, your metric might be “10 new donors per email” or “$500 raised per email.”

Depending on your goals, methods might include surveys, interviews, web analytics, focus groups, voting data, or policy reviews. Choose tools that offer reliable insights without overwhelming your team.

Measure to Learn, Not Just to Prove Evaluation should serve your learning agenda. Frame your storytelling project around a strategic question: Which story formats generate the most engagement? What messages increase donor conversion? To answer such questions, compare data before and after deployment, or run A/B tests. For instance, send different story-based emails to equal groups—one featuring a community member, the other a staff leader—and compare response rates.

Refine your approach as you learn. Iterate. The goal is improvement, not perfection.

Don’t Evaluate Without Intention Like grant writing, evaluation forces clarity. It helps you articulate what matters—and why. But evaluation without a learning strategy is like telling only the end of a story: You report the outcome but omit the journey.

If you don’t expect to use what you learn, or lack capacity to act on it, skip it. That’s the guidance of a 2014 Stanford Social Innovation Review piece: Don’t waste energy on evaluation that serves no purpose.

Stories as Evidence Storytelling itself can be a form of evaluation. For example, GlobalGiving’s Storytelling Project trained community members to gather over 57,000 micro-narratives in Kenya and Uganda. These stories were then analyzed to identify needs, highlight innovations, and assess community strengths. This approach isn’t only for global NGOs—any group can use stories to reflect, learn, and document impact.

Gather stories to assess needs and strengths and document impact.

“Rebecca’s life has come to an end with doctor’s announcement that she was pregnant…” That’s the first line of one of over 57,000 “micro-narratives” collected in Kenya and Uganda by GlobalGiving, a website that allows users to donate to vetted development projects around the world. The organization’s Storytelling Project hires and trains “scribes” to gather stories in the areas where beneficiary groups are located. Those stories get fed through a host of tools GlobalGiving created to filter data about community needs, possible solutions, and innovative organizations that it might add to its web platform. The data also supports other groups in international development, especially the small ones that can’t afford such a project, so one funder tells the Stanford Social Innovation Review. And the project’s principle applies to groups of any size: Gathering stories can help a group assess the needs and strengths of the community in which it works and document its impact.

Further exploration:

- Chapter from Hatch on evaluation has tips about how to create good key progress indicators, or KPIs.

- How Do We Know is a project of Active Voice Lab and has resources on evaluating how media contributes to social change.

- Animating Democracy, a project of Americans for the Arts, has a page on social-impact indicators, and a broader set of a resources.

- Narrative Arts has a blog post on using the social-impact indicators of Animating Democracy to evaluate storytelling work.