How do we tell stories about the future we want to see?

Credit: Center for Artistic Activism

A very unscientific survey of nonprofit stories reveals that, oh, 95 percent of them take place in the past. Stories of voter suppression can stir people to action. Stories of how LGBTQ adults are thriving can inspire young people to stick around until things get better. And yet much of what nonprofits do is focused on the future. But what does the future that we’re trying to create actually look like?

“Most movements from the early days of my activism could be summed up by ‘No, we’re against it.’ There was very little of ‘Yes, this is what we’re for,’” says Steve Duncombe, co-founder and co-director with Steve Lambert of the Center for Artistic Activism (CAA).

Stories of a better future have been among the most powerful documents in history, Duncombe says, from the Bible’s depiction of heaven, to Plato’s imagining of the Republic, to Thomas More’s renderings in Utopia. (And let’s not forget Martin Luther King Jr.’s riveting dream.) In the insightful introduction to his open online edition of More’s 1516 book, Duncombe says: “The dominant system dominates not because people agree with it; it rules because we are convinced there is no alternative. Utopia offers us a glimpse of an alternative.”

I think hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and…even imagine some real grounds for hope… Poets, visionaries—the realists of a larger reality. – Ursula Le Guin, in her 2014 National Book Award acceptance speech

So how can we tell stories to bring about the future we envision?

Imagine it.

We’ve had our imaginations constricted by endless meetings, jargon, grant proposals, and all the rest. According to Duncombe, “We’re under the tyranny of the possible.”

To overthrow that tyranny, the CAA leads workshops called “Imagining Utopia.” The workshops start off with a slideshow of 19th-century images of what the 21st century would look like. “Flying cars and all that stuff. It helps participants break out and imagine fully,” says Duncombe. Workshop leaders then ask what victory looks like. At a workshop for a health organization, the answer might be “a cure for hepatitis C”—at which point the workshop leaders will prompt participants to think bigger. Once they get to the really big picture—“We want people to be healthy so they can enjoy a good life”—the CAA duo might ask, “What does a good life look like? Take us on a tour of your neighborhood,” and then trace things backward from there.

This process helps people put discrete advances, such as curing hep C, in the context of a larger vision. “The Utopian answer to power is to redefine power and what a good society is,” Duncombe says. “And those visions, when shared by enough people, actually do undermine power.”

Draft it.

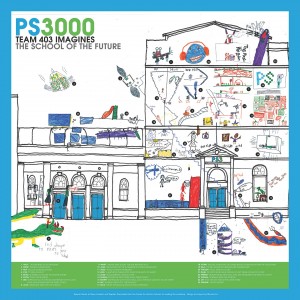

Tell your story of the future using collage, photography, drawing, or writing. The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture—a nonprofit organization, not an actual government agency—sponsors “Imaginings” to bring together artists, organizers, and community members to imagine what their communities might look like in 20 years.

Steve Lambert once collaborated with other artists and writers to produce a free New York Times Special Edition, published in 2008 but dated 2009. The paper was full of “All the News We Hope to Print,” such as the end of the Iraq war and the passage of a “Maximum Wage Law,” and each story contained ideas on how grassroots activism could drive the change.

Members of the Hypothetical Development Organization selected a dozen buildings in New Orleans that had fallen into disuse and invented a “hypothetical future” for each one, unbounded by “commercial potential, practical materials, or physics.” Renderings of each building were posted out front of the building, displayed in a gallery show, and offered for sale as prints.

Enact it.

Telling stories about a better future puts that future forever out on the horizon. What if you could act out the future now? Writing in Beautiful Trouble, a project on creative activism, Andrew Boyd says you can, by doing what he calls “prefigurative intervention”—actions that “create a little slice of the future we want to live in.”

Whenever we try to envision a world without war, without violence, without prisons, without capitalism, we are engaging in speculative fiction. All organizing is science fiction. – Walidah Imarisha, introduction to Octavia’s Brood

He sees the lunch counter sit-ins of the 1960s as an example: “[They were] defiant, courageous and ultimately successful acts of resistance against America’s Jim Crow-era apartheid…but they also…prefigured the world they wanted to live in: they were enacting the integration they wanted.” More recent examples Boyd cites include Occupy encampments around the world, which he sees as a “microcosm [of] the communitarian and democratic world they want to bring into being.” According to Boyd, “We can’t create a world we haven’t yet imagined. Better if we’ve already tasted it.”

Further exploration:

- “Visioning” exercises from the Advantage Initiative—a group working to improve communities for an aging society—including guided imagery and collage.

- Cover Story (PDF), a shared-vision exercise created by COOL and Idealist in which people create a magazine cover or front page of a newspaper from a possible future. A group in North Carolina did the exercise.

- Could Be, a program produced by United Nations Radio and broadcast on NBC in 1949, imagined what could be if countries focused on peace.

- “The Future Is Now,” the opening-night event of the 2015 PEN World Voices Festival, had writers from around the globe imagine the best- and worst-case scenarios for the world in 2050. Full audio and video here.

- Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories From Social Justice Activists, edited by Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown. The editors offer presentations and workshops on writing science fiction and visionary fiction.